Wellbeing

The goal: 6/10 or more

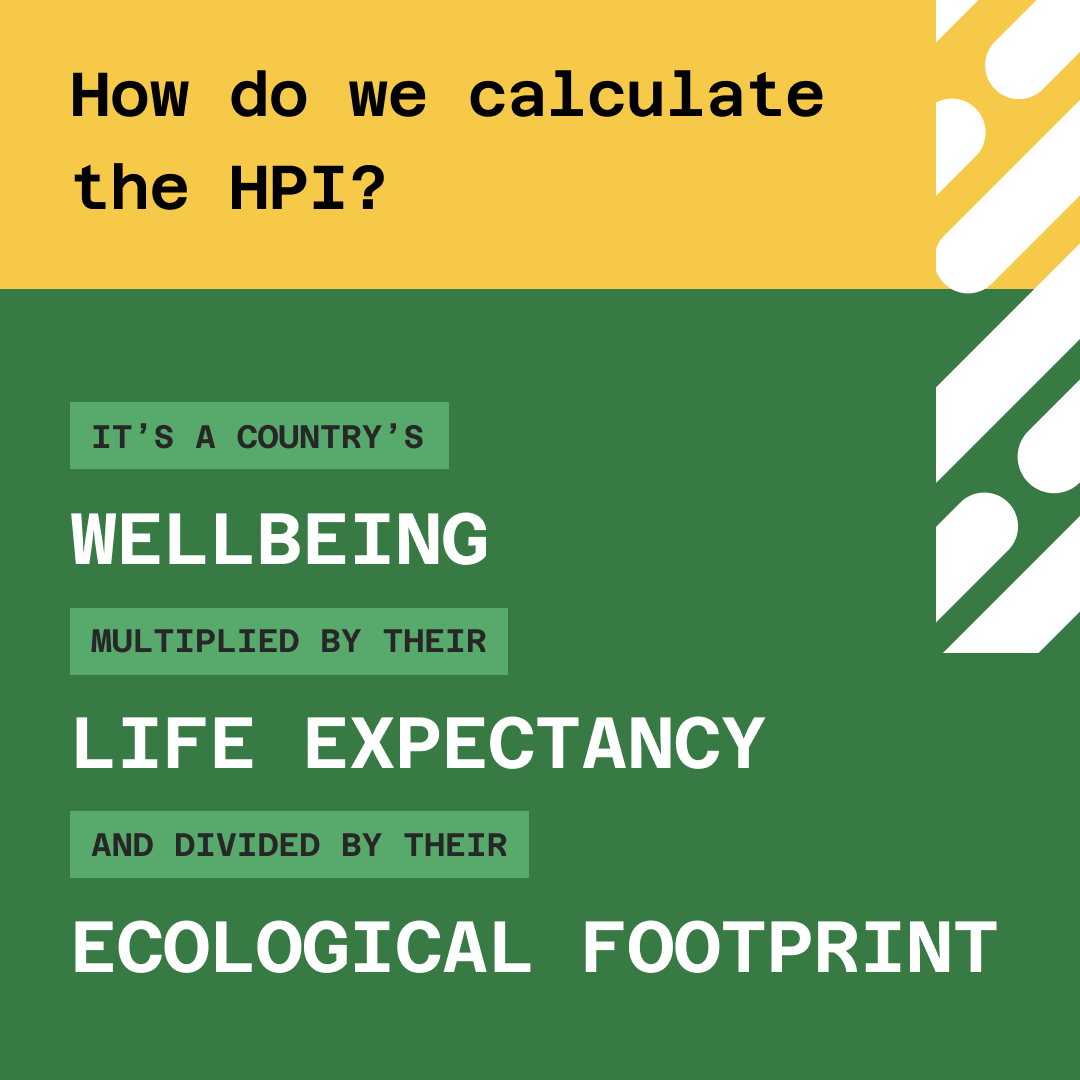

The Happy Planet Index (HPI) combines three elements to show how efficiently residents of different countries are using environmental resources to lead long, happy lives.

We use a traffic light system – red, amber, and green – to show how well countries score on each element.

Before combining the three components, we make adjustments to ensure that no single component dominates the overall calculations. Details can be found in the methodology paper.

The goal: 6/10 or more

The goal: 75 years or more

The goal: Below or at per capita biocapacity (1.56 gha for 2019)

The Happy Planet Index (HPI) is not an indicator of the happiest country on the planet, or the best place to live. Nor does it indicate the most developed country in the traditional sense, or the most environmentally friendly. Instead, the HPI combines these ideas, offering a method of comparing countries’ progress towards the goal of providing long-term wellbeing for all, without exceeding the limits of the planet’s resources.

The Happy Planet Index inevitably does not answer every question.

What the Happy Planet Index does do is to serve as a compass pointing in the overall direction in which societies should be travelling – towards higher wellbeing lifestyles with lower ecological footprints. It attempts to do this in as simple a way as possible, without being simplistic.

To measure wellbeing, we use data from a globally renowned survey, the Gallup World Poll, which asks respondents questions about how they feel their lives are going overall. The question we use, known as the ‘Cantril Self-Anchoring Scale’ or the ‘Ladder of Life’, has been used in surveys since the 1960s, and its validity has been demonstrated in a range of different contexts around the world.

Importantly, asking a single broad question allows the people completing the survey to assess the issues according to their own criteria, to weigh each one as they choose, and to produce an overall response.

There is a growing evidence-base showing that subjective measures of wellbeing, like ‘the Ladder of Life’ correlate with more objective measures such as measurement of stress hormones and brain scans. Subjective wellbeing has been found to accurately predict a range of outcomes – from how long someone will stay in a job or stay married, to how long they live, to the results of elections.

As a result, psychologists, sociologists, and economists now regularly use subjective wellbeing data in research, and policy makers are beginning to use it to inform decision-making. One example is the Wellbeing Economy Governments collaboration, in which national and regional governments share expertise and transferrable policy practices aimed at creating sustainable wellbeing.

Many countries may do well on the Happy Planet Index rankings despite their political systems, rather than because of them.

Governments are, of course, partly responsible for a country’s HPI score. Governments can introduce policy to reduce emissions, improve healthcare to increase life expectancy, or tackle economic inequalities to improve average wellbeing. But a country’s HPI score is not entirely determined by the actions of its present government.

Changes in wellbeing and life expectancy can take years to evolve. Investments in education take decades to bear fruit, particularly as the HPI does not use self-reported wellbeing data from children. Even past governments cannot be held wholly responsible for a country’s HPI score. Cultural factors and social capital have evolved over centuries and these too, strongly shape the country’s outcomes. Lastly, of course, one cannot ignore basic geographical and climate factors. To achieve a low ecological footprint is inevitably harder in countries which face extreme hot or cold temperatures, than in those that have more temperate climates.

All these factors mean that we should not be too surprised when there are countries that do well on the HPI, despite undemocratic or corrupt governments.

In the 2016 edition of the Happy Planet Index, life expectancy and wellbeing were adjusted for inequality. This meant two countries which had the same average life expectancy or wellbeing would score differently on the HPI if they had different levels of inequality.

To be able to make this adjustment, we used full life tables which allowed us to determine the inequality of life expectancy within a country, and the distributional data on wellbeing. The latter was not available for us for all years at the time of preparing the current version of the HPI, so we were unable to adjust HPI scores for inequality.

Having said that, evidence suggests that income inequality (which is perhaps the inequality that most people are concerned about), is associated with both average wellbeing and life expectancy. In other words, all else being equal, countries with higher income inequality will have lower average wellbeing and lower average life expectancy. As such, even without explicitly adjusting for inequality, the HPI can be seen to at least indirectly capture this factor.

The 2021 Happy Planet Index is the fifth edition of the index and this year, we have included time trends starting from 2006. However, the earlier published editions (2006, 2009, 2012 and 2016) all used slightly different methodologies and data sources, so they are not directly comparable over time.

There are three main reasons why different editions of the HPI cannot be directly compared.

Firstly, the last edition of the HPI (published in 2016) used inequality adjusted measures of wellbeing and life expectancy. This has not been possible for the current edition of the HPI. Inequality adjustment affected the relative scores of countries, but generally led to lower scores across the world, simply because of the methodology used. So the highest HPI score in the last edition of the HPI was 44.7 (for Costa Rica), whereas in this edition, in 2019, Costa Rica scored 62.1.

Secondly, the ecological footprint data produced by the Global Footprint Network is constantly improving. This also means that the estimates for countries’ ecological footprints for earlier years have been revised. Comparing the ecological footprint data that we used in this edition of the HPI for the year 2012, with the data for the same year that was used in the previous edition of the HPI, one can see that on average, country footprint estimates differed by 0.24 global hectares (gha) per person. In some cases, the change in the estimate was quite substantial. For example, the 2016 edition of the HPI used an ecological footprint for Switzerland of 5.79 gha. In this edition, Switzerland’s per capita footprint in 2012 was 5.06 gha. Meanwhile, the estimated footprint for Bhutan almost doubled (from 2.32 gha to 4.56 gha).

Thirdly, we make adjustments to each component before combining them into the HPI. These adjustments are a form of standardisation aimed at equivalising the amount of variance for each of the three components. The precise adjustments have therefore varied from edition to edition.

There is often migration out of countries with higher Happy Planet Index scores to those with lower scores, like in Mexico to the USA (54.3 vs. 37.4), or from Morocco, where the HPI score is 50.9, to Denmark (which has a score of 45.3) or to Belgium (which has a score of 42.5).

Does this suggest that the Happy Planet index is ‘incorrect’? Definitely not.

Unlike other indices, such as the Quality of Life Index or World Happiness Report, the Happy Planet Index does not rank countries in terms of quality of life or happiness.

The HPI is a measure of the sustainability of a country’s wellbeing, not a measure simply of its wellbeing. It ranks countries by how efficiently people use our limited ecological resources to live long, happy lives. We look at how countries use minimal ‘inputs’ of natural resources to create the maximum possible ‘outputs’ of long, happy lives – thus delivering truly “sustainable wellbeing”.

The Happy Planet Index does not consider societies that deliver “good lives” which use more resources than the earth can support, to be truly successful. At the same time however, it does not consider societies that have a per capita ecological footprint that is within the Earth’s limits, but which have very low levels of wellbeing or life expectancy to be efficient.

So while it is true that countries that typically see higher immigration (e.g. the USA, Denmark, and Belgium) generally have higher life expectancy and wellbeing than in the countries from which people migrate (e.g. Mexico and Morocco), they often do so at a very high cost to the Earth.

Whilst the 2020 Happy Planet Index data provide a tantalising glimpse into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the globe’s ability to achieve sustainable wellbeing, it must be interpreted with caution, due to missing and estimated data. We have had to make estimations or to deal with missing data for 2020 for all three components of the HPI. As such, whilst we encourage people to look at the changes for individual countries from 2019 to 2020, we did not believe it appropriate to focus attention on the 2020 rankings.

Firstly, in terms of life expectancy, actual data on life expectancy in 2020 was only available for 36 countries. For all the other countries for 2020, we have used estimates of the change in life expectancy due to the pandemic from an academic paper (Heuveline & Tzen, 2021). We compared the estimates with the actual life expectancy changes for the 36 countries: whilst, the estimates have proven relatively accurate for wealthier countries, we have found substantial deviations for lower income countries. As actual life expectancy data for 2020 comes in, we may see substantial differences from what we have estimated for many countries.

Secondly, figures for the ecological footprint for 2020 are very preliminary. The Global Footprint Network itself has only calculated ecological footprint up until 2017. We are fairly confident about the estimates we have made for 2018 and 2019, as these are based on a model using many years of data and country-level changes in CO2 emissions for those years. However, for 2020, we relied upon the broad estimate of the global decline in ecological footprint of 6.5% from 2019 to 2020 from the Earth Overshoot Day 2021 report. To estimate the relative changes for different countries, we used CO2 emission data from the bp Statistical Review of World Energy, which is not available for all countries.

Thirdly, in terms of wellbeing, wellbeing data was only available for 94 countries (the 2019 ranking includes 152 countries). Unlike with ecological footprint and life expectancy, we chose not to estimate wellbeing for any countries for 2020. As such, many countries, including top ranking Costa Rica, are not included in the 2020 data set. Furthermore, even when wellbeing data was available for 2020, one must be cautious about interpreting differences between countries and changes over time. Differences between countries may be partially explained by differences in the timing of the Gallup World Poll survey in different countries. Whether a country was mostly surveyed before a global pandemic was declared (e.g. Australia), during the peak of the spring wave (e.g. the Netherlands), or in the summer when life had returned to relative normality in many places (e.g. Italy) is likely to have influenced the average wellbeing reported. In terms of change over time, there is a risk that changes in mode of administration (which was necessitated in many countries due to lockdown measures) may have contributed to the changes in the average wellbeing scores reported.

While some countries are more efficient than others at delivering long, happy lives for their people, every country has its problems and no country performs as well as it could.

A good score on the HPI does not suggest that there are no problems in a country, that distribution of wellbeing or resource consumption is equitable, or that current levels of wellbeing and consumption are sustainable.

Human rights abuses

Human rights abuses are a problem in most of the world, including in some of the high-ranking countries in the Happy Planet Index results. While the HPI may reflect some of the negative impacts of human rights abuses and inequality, it does not seek to directly measure this.

The wellbeing and life expectancy data used to calculate The Happy Planet Index scores for each country capture an overall sense of how people are doing in a nation. Although the infringement of human rights negatively impacts on the wellbeing and life expectancy of some people in a country, the Happy Planet Index is based on average figures for the population as a whole. As it is likely that people directly affected by extreme human rights abuses represent a minority, the population average wellbeing score may not fully reflect this harm.

More information about human rights abuses around the world can be found on the Amnesty International website.

Inequality

People across the world are experiencing the impact of growing inequalities – both in terms of the underlying failures of social justice, and the negative effect it has on other outcomes.

The Happy Planet Index scores for each country capture an overall sense of how people are doing in a nation based on average figures for the population as a whole. Of course, averages can hide stark inequalities, and most people would see it better for a country to have, for example an equally distributed high life expectancy, than a very unequal distribution of life expectancy even if the average is high.

Having said that, the outcome measures we use – i.e. average life expectancy and average subjective wellbeing, are known to be negatively influenced by large income inequalities. So it is likely that, all else being equal, countries where economic inequality goes down will see improvements in the HPI, and vice versa.

We rely on the availability of robust data from the United Nations, Gallup World Poll, and the Global Footprint Network to calculate the Happy Planet Index score for each individual country. Unfortunately, that data isn’t available for every country.

We believe that being happy is good for everyone and that promoting human happiness does not need to be at odds with creating a sustainable future. We've built this personal Happy Planet Index test to help you reflect on how you can create your own "good life that doesn't cost the earth".

Take the testUse our promotion pack to start the conversation: “How can we live good lives that don’t cost the Earth?”

Happy Planet Index promotion pack